"Orchestrating Mammalian Tissue Healing at the Organ Scale"

Dr. Yvon Woappi | Woappi Lab

Dr. Yvon Woappi | Woappi Lab

Bio:

Dr. Yvon Woappi is the Herbert and Florence Irving Assistant Professor of Physiology and Cellular Biophysics, Dermatology, and Biomedical Engineering at Columbia University. His research leverages gene editing and multiomic technologies to uncover how autonomous multicellular orchestration facilitates deep wound repair – a process critical to many conditions including diabetic ulcers and carcinomas. Dr. Woappi earned his Ph.D. as a Grace Jordan McFadden Fellow at the University of South Carolina and completed his postdoctoral training in the Harvard Dermatology Research Training Program at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Woappi’s pioneering early-career research is laying the foundation for synthetic wound regeneration, a systems bioengineering approach that leverages cellular heterogeneity to enhance tissue regeneration.

Abstract:

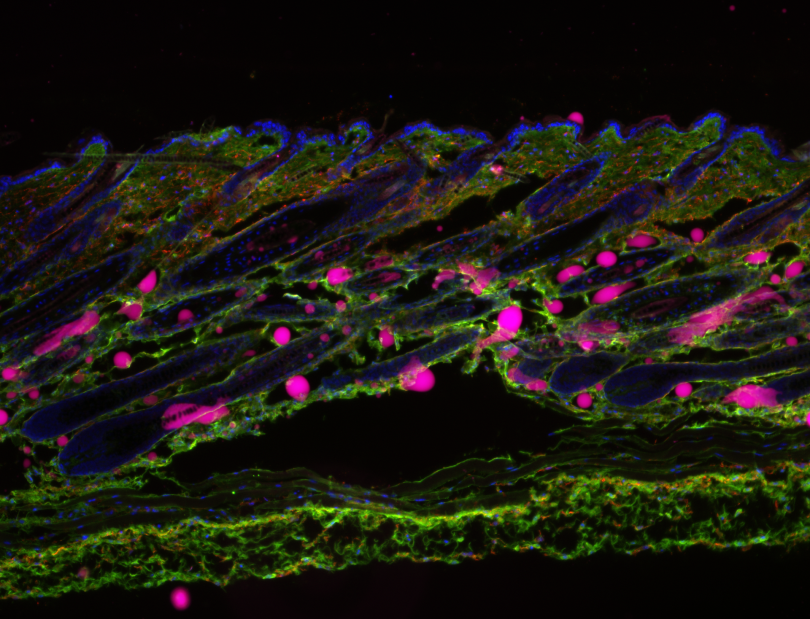

As the organ most frequently exposed to predatory pressures, the integument has acquired broad functions, including camouflage, thermoregulation, sensory perception, and tissue repair. These roles are executed through a complex interplay of tissue substructures, including several mini-organ appendages (hair follicles, sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscle, and assorted pilosebaceous units) and five central adnexal structures (blood vessels, sensory neurons, collagenous tissues, immune components, and deep fascia), all embedded within three superimposed tissue strata (the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis). Given this intricate architecture, the healing of deep skin wounds requires a coordinated organ-level response involving varied cell populations originating from virtually all three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. However, a comprehensive understanding of the cellular and molecular logic orchestrating this crosstissue response in mammals remains incomplete. Here, we present the Organ-Scale Wound Healing Atlases (OWHA), a comprehensive multiomic single-cell and spatial transcriptomic dataset that captures the dynamic microanatomical tissue niches of the mammalian integument during the entire wound healing sequence, including early and late healing phases. By incorporating multi-omics data across all major phases of healing, OWHA uncovered novel emergent healing cell states and their coordinated cell fate decisions uniquely (multilineage crosstalk) executed after injury, and delineated critical tissue trajectories required for eKective healing of deep wounds. Importantly, comparative analysis between human and mouse revealed conserved network between the epithelial and neuro-endothelial vasculature....(Add missing groups in human only found in our multi modal approach) By providing deeper mechanistic insights of mammalian tissue adaptations for injury response, OWHA serves as a valuable resource for understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying wound healing in the mammalian integument.